Super-Resolution Microscopy:

Principle, Applications, and ibidi Solutions

What Is Super-Resolution Microscopy?

Super-resolution microscopy is a powerful imaging technique that overcomes the traditional diffraction limit of light microscopy, achieving resolutions beyond the classical ~200 nm barrier. By employing sophisticated optical and computational strategies, super-resolution microscopy enables the observation of structures at the nanoscale. This breakthrough effectively transforms conventional light microscopy into "nanoscopy", allowing detailed exploration of biological and molecular structures previously invisible under a standard microscopes.

The most prominent super-resolution methods which can reach resolutions down to the nanometer scale are stimulated emission depletion (STED), minimal fluorescence photon fluxes (MINFLUX) and single molecule localization microscopy (SMLM)—including photoactivated localization microscopy/direct stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (PALM/dSTORM) and DNA points accumulation for imaging in nanoscale topography (DNA-PAINT).

Other super-resolution methods, for which the resolution enhancement is less pronounced, are expansion microscopy (ExM) and structured illumination microscopy (SIM).

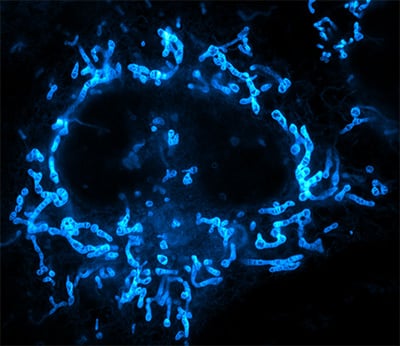

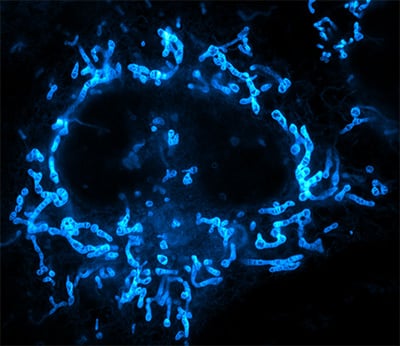

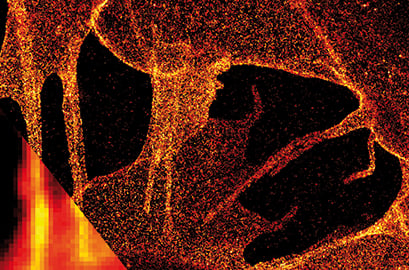

Mitochondria in a live adherent human cancer cell (HeLa). Cells were stained with the fluorescent probe PK Mito Orange and recorded on a stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscope (Abberior Instruments Expert Line) using 561 nm excitation and 775 nm depletion light and an UPlanSApo 100×/1.40 Oil objective. The cells were cultured and recorded in an ibidi µ-Dish 35 mm, high Glass Bottom. Image by courtesy of Till Stephan, Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany

What Is Super-Resolution Microscopy Used For?

Super-resolution microscopy is widely used in fields such as cell biology, neurobiology, and molecular biology, to understand structures and dynamics at the nanoscale. It allows researchers to study protein localization, cellular architecture, molecular interactions, and dynamic processes in living cells with exceptional clarity. This capability pushes discoveries in understanding diseases, cellular functions, and biomolecular mechanisms.

SUPER RES ÜBERSICHTSBILD

S.J. Sahl, S.W. Hell, S. Jakobs. Fluorescence nanoscopy in cell biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017; 18:685–701. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.71

B. Huang, H. Babcock, X. Zhuang. Breaking the diffraction barrier: super-resolution imaging of cells. Cell. 2010; 143(7):1047 – 1058. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.002

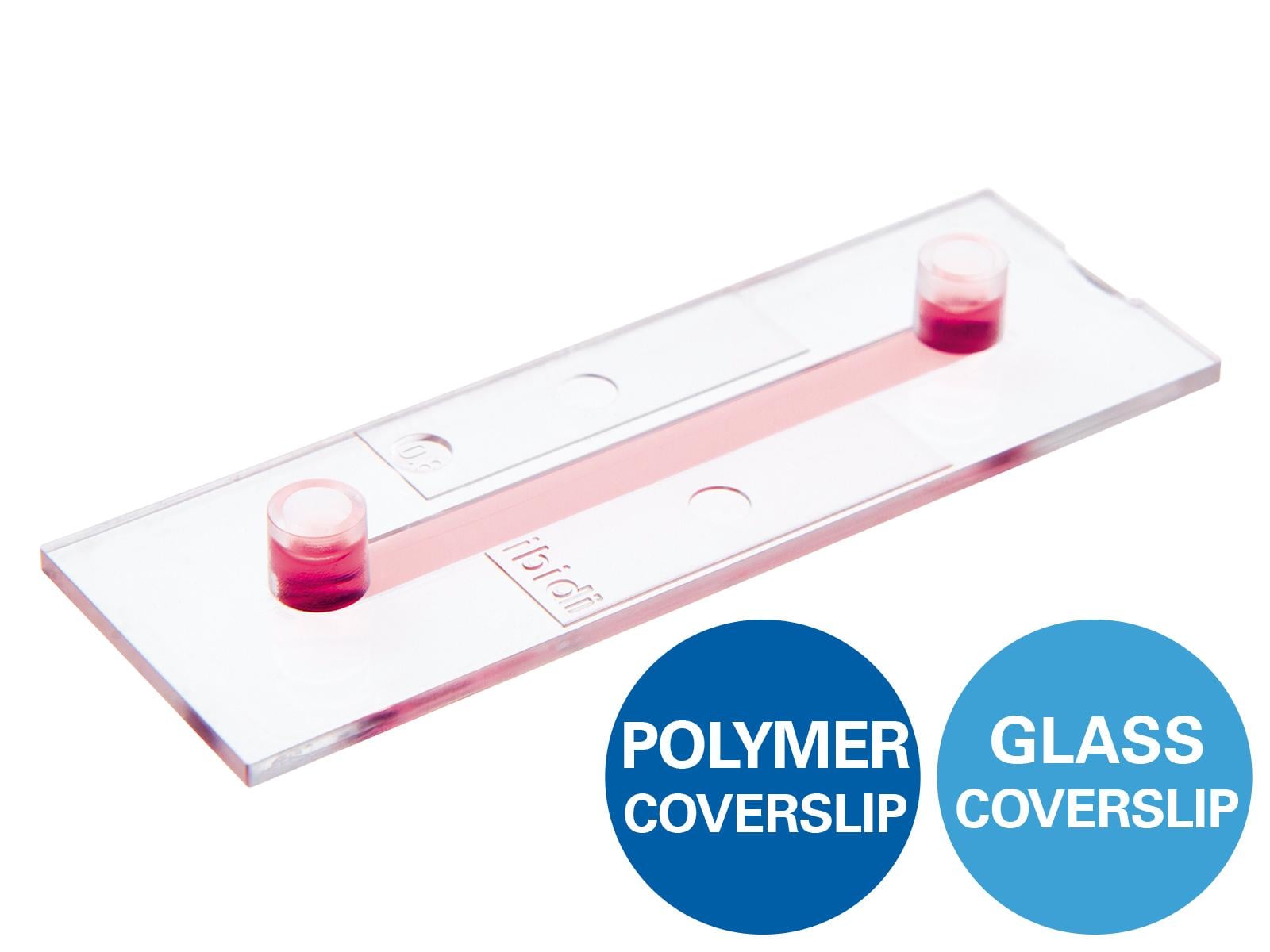

Which ibidi Products Can Be Used for Super-Resolution Microscopy?All ibidi µ-Slides, µ-Dishes, and µ-Plates with an ibidi #1.5H Glass Coverslip bottom are fully compatible with super-resolution microscopy. For SLM, especially the ibidi Channel Slides can be beneficial for precise blinking buffer application and control. If you plan to use labware with the ibidi #1.5 Polymer Coverslip bottom for super-resolution applications, we recommend testing it first with the ibidi Free Sample Program. Find more information about the ibidi coverslip bottoms in our Application Chapter. |

|

How Does Super-Resolution Microscopy Work?

Breaking the diffraction limit, which restricts the resolution of conventional light microscopes, can be achieved through several conceptual strategies. High-resolution enhancement can be obtained by actively shaping the point spread function (PSF) (e.g., STED) or by computational reconstruction of a time series of sparse signals (SMLM). In contrast, techniques based on computational reconstruction of spatial frequency information (SIM) or physical expansion of the sample (ExM) typically yield moderate resolution improvements.

HAPPY CELL | The point-spread function (PSF) describes how an imaging system—because of diffraction and scattering of light—spreads the beam from a perfect point into a blur. The smaller and sharper the PSF, the higher the system’s optical resolution. |

- PSF-shaping: STED actively reduces the lateral extent of the PSF using stimulated emission depletion, allowing sub-diffraction imaging down to approximately 20 nm.

- Computational reconstruction of a time-series of sparse signals: SML techniques, such as PALM, dSTORM and DNA-PAINT rely on the sparse and stochastic signals of fluorophores. By detecting individual emitters over time and precisely localizing each emission event, these methods reconstruct a super-resolved image with resolutions down to approximately 5–80 nm.

- Computational reconstruction of spatial frequency information: Structured illumination microscopy (SIM) uses patterned excitation light to encode high spatial frequencies, which are then computationally reconstructed to achieve roughly a twofold improvement in resolution over conventional widefield imaging.

- Physical expansion of the sample: Expansion microscopy (ExM) physically enlarges the specimen by embedding it in a swellable polymer. This effectively increases the distance between structures, allowing conventional microscopes to resolve features that would otherwise be below the diffraction limit.

What is STED Microscopy?

Stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy is a deterministic super-resolution technique that uses two synchronized laser beams: an excitation laser that brings fluorophores into the excited state, and a red-shifted, doughnut-shaped depletion laser that forces excited molecules back to the ground state via stimulated emission. The depletion laser reduces fluorescence around the periphery of the excitation spot, effectively shrinking the point spread function (PSF). This process enables a lateral resolution of approximately 20–50 nm or better, depending on the power of the depletion laser and the properties of the fluorophores.

Hell, S.W.. Far-Field Optical Nanoscopy. Science, 2007; 316(5828):1153-1158. doi: 10.1126/science.1137395

Thomas A. Klar et al. Fluorescence microscopy with diffraction resolution barrier broken by stimulated emission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 2000; 97 (15) 8206-8210, doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8206

Mitochondria in a live adherent human cancer cell (HeLa). Cells were stained with the fluorescent probe PK Mito Orange and recorded on a stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscope (Abberior Instruments Expert Line) using 561 nm excitation and 775 nm depletion light and an UPlanSApo 100×/1.40 Oil objective. The cells were cultured and recorded in an ibidi µ-Dish 35 mm, high Glass Bottom. Image by courtesy of Till Stephan, Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany

MINFLUX: Combines the Best of STED and SMLM Techniques

MINimal FLUorescence photon FLUXes (MINFLUX) is an advanced super-resolution technique that pushes localization precision into the 1–5 nm range. This technique combines concepts from deterministic STED microscopy and stochastic SMLM approaches. Instead of illuminating the fluorophore broadly, MINFLUX uses a single doughnut-shaped excitation beam whose central intensity minimum serves as the reference point for localization. The excitation minimum is moved in a defined pattern around a blinking fluorophore, and the system measures how many photons are emitted at each position. When the beam is perfectly aligned with the fluorophore, no emission photons are detected. A slight shift in the beam's position causes emission, revealing the molecule's location. This approach enables extremely high localization precision, low photon budget, high temporal resolution, and highly efficient single-molecule tracking.

New developments such as MINFLUX-PAINT combine the multiplexing capabilities of DNA-PAINT with the localization precision of MINFLUX.

Schmidt, R. et al. MINFLUX nanometer-scale 3D imaging and microsecond-range tracking on a common fluorescence microscope. Nat Commun, 2021; 12, 1478. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21652-z

Ostersehlt, R. et al. DNA-PAINT MINFLUX nanoscopy. Nat Methods, 2022; 19, 1072–1075. doi: 10.1038/s41592-022-01577-1

What is SML Microscopy?

Single-molecule localization microscopy (SMLM) techniques rely on the sparse “blinking” of fluorophores and time-series detection, to prevent overlap of the PSFs of the individual target molecules. The most prominent SMLM techniques are:

- PALM (photoactivated localization microscopy)

- dSTORM (direct stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy)

- DNA-PAINT (DNA points accumulation for imaging in nanoscale topography)

In SMLM, a time series of the sample is recorded while fluorophores labeling the target molecules “blink” in a controlled—often stochastic—manner, ensuring that only a sparse subset of fluorophores emits in any given time frame (ideally only one emitter per diffraction-limited area). The center of each emission spot is then localized with sub-diffraction precision. By accumulating many frames, a super-resolved map of all blinking events can be reconstructed.

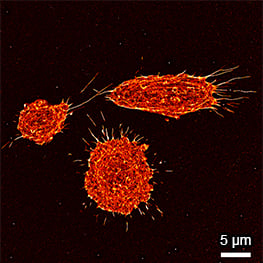

dSTORM image of plasma membrane glycans on the ibidi Polymer Coverslip. Membrane glycans of SK-N-MC neuroblastoma cells were stained through the metabolic incorporation of azido-sugar analogues followed by copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC). Inlet: comparison to widefield microscopy. Provided by Markus Sauer, Würzburg

What Is the Difference between PALM, dSTORM and DNA-PAINT?

PALM is based on photoactivatable or photoconvertible fluorescent proteins that can be switched from a dark to a fluorescent state in a controlled manner, to control that only a sparse subset of molecules is fluorescent at any given moment. The blinking arises because each activated fluorophore emits only once or a few times before bleaching. PALM typically achieves lateral resolutions of approximately 20–30 nm and offers key advantages for live-cell imaging, endogenous protein tagging, and applications where genetically encoded labels minimize perturbation of the biological system.

dSTORM uses conventional organic dyes that can reversibly switch between fluorescent and dark states under specific chemical buffer conditions. These buffers induce the stochastic “blinking” ensuring sparse single-molecule emission suitable for localization. dSTORM also reaches lateral resolutions of around 20–30 nm.

DNA-PAINT uses transient binding of short, fluorescently labeled DNA strands in solution (“imager strands”) to complementary DNA strands attached to the target (“docking strands”). The characteristic “blinking” arises from the binding and unbinding kinetics of the DNA strands. By collecting many such events in a time series, individual molecules can be localized with nanometer precision. DNA-PAINT pushes the resolution limit to 15–10 nm. Further developments of DNA-PAINT include:

- RESI (resolution-enhanced sequential imaging): reaches Ångström-level resolution by sequentially labeling identical targets with different docking strands

- Exchange-PAINT: enables virtually unlimited multiplexing by washing different imager strands in and out sequentially.

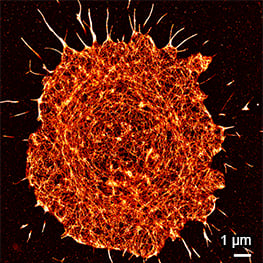

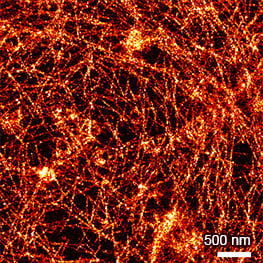

Super-resolution PAINT microscopy of fixed B cells in the µ-Slide VI 0.5 Glass Bottom, using a TIRF microscope. Massive-Actin (Cy3B) was used to visualize the F-actin cytoskeleton. Objective lens: Nikon CFI SR HP Apochromat TIRF 100x Oil immersion, NA=1.49. Courtesy of Massive Photonics GmbH (www.massive-photonics.com).

Lelek M. Single-molecule localization microscopy. Nat Rev Methods Primers, 2021; 1(39). doi: 10.1038/s43586-021-00038-x

Piantanida L, Li ITS, Hughes WL. Advancements in DNA-PAINT: applications and challenges in biological imaging and nanoscale metrology. Nanoscale. 2025; 17(23):14016-14034. doi: 10.1039/d4nr04544k

Reinhardt, S.C.M., Masullo, L.A., Baudrexel, I. et al. Ångström-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Nature, 2023; 617, 711–716. doi: s41586-023-05925-9

Agasti SS, et al. DNA-barcoded labeling probes for highly multiplexed Exchange-PAINT imaging. Chem Sci. 2017; 8(4):3080-3091. doi: 10.1039/C6SC05420J

What is Structured Illumination Microscopy?

Structured Illumination Microscopy (SIM) is a super-resolution technique that uses patterned excitation light to extract otherwise inaccessible spatial information from a sample. By illuminating the specimen with a well-defined pattern, at multiple phases and orientations, SIM encodes high-frequency structural details into lower-frequency components that can be captured by the microscope. During computational reconstruction, this information is decoded and recombined to generate a higher-resolution image. SIM typically provides a two-fold increase in resolution compared to conventional widefield microscopy, while maintaining relatively low light doses, fast acquisition, and excellent compatibility with live-cell imaging.

Heintzmann R, Huser T. Super-Resolution Structured Illumination Microscopy. Chem Rev, 2017; 117 (23):13890-13908. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00218

What is Expansion Microscopy?

Expansion Microscopy (ExM) is a super-resolution technique that physically enlarges the sample to enhance imaging resolution. The specimen is chemically anchored to a swellable polymer network—commonly a sodium acrylate–acrylamide hydrogel—which is then isotropically expanded by absorbing water. As the hydrogel expands, the distances between fluorescent labels expand as well, allowing conventional fluorescence microscopes to resolve features that would normally be diffraction limited. ExM typically provides a 2–4-fold improvement in effective resolution, depending on the expansion factor. However, when combined with SML methods such as DNA-PAINT (ExM–PAINT), the physical expansion of the sample and the high localization precision of PAINT synergize to achieve extremely high effective resolutions, approaching the lower nm-scale.

Zwettler, F.U., Reinhard, S., Gambarotto, D. et al. Molecular resolution imaging by post-labeling expansion single-molecule localization microscopy (Ex-SMLM). Nat Commun, 2020; 11, 3388 doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17086-8

What Are the Advantages and Limitations of the Different Super-Resolution Techniques?

Technique | Lateral optical effective resolution | Advantages | Limitations |

STED | ~20–50 nm | Fast imaging; no complex post-processing; can be compatible with live-cell imaging; high temporal resolution | Requires high depletion laser power; photobleaching and phototoxicity possible; |

MINFLUX | ~1–5 nm | Ultra-high localization precision; minimal photon budget; fast acquisition; excellent for single-molecule tracking | Requires extremely stable instrumentation and precise alignment |

MINFLUX-PAINT | ~1–3 nm | Extremely high resolution, Highly suitable for multiplexing | Requires DNA labeling strategies and specialized MINFLUX instrumentation; not suitable for live cells |

PALM | ~20–30 nm | Ideal for live-cell imaging; low laser power needed; minimal phototoxicity | Limited fluorophore brightness and photon budget; slower acquisition |

dSTORM | ~20–30 nm | High photon yield; excellent for fixed samples; wide availability of antibody labeling | Requires thiol-based switching buffers; not suited for live-cell imaging; slow acquisition |

DNA-PAINT | ~5–10 nm | Extremely high localization precision; low light intensity needed; flexible labeling | Slow acquisition; requires not suited for live-cell imaging |

RESI | Ångström-level | Molecular-scale localization | Requires multiple imaging cycles; complex DNA labeling; long acquisition times |

Exchange-PAINT | ~5–10 nm | Virtually unlimited multiplexing | Slow acquisition; extensive sample preparation; not suitable for live-cell imaging |

SIM | ~100–130 nm | Fast imaging; low light intensity needed; excellent for live-cell and multicolor imaging; minimal phototoxicity | Moderate resolution improvement; requires patterned illumination and reconstruction algorithms |

ExM | ~50–100 nm | Works with standard microscopes; inexpensive hardware requirements | Requires extensive sample preparation; only fixed samples; resolution limited by expansion factor and isotropy |

ExM-PAINT | ~5–10 nm | Very high resolution; excellent for dense or complex structures | Long workflows; requires DNA docking labeling and expansion chemistry; not suitable for live cells |

How To: Practical Tips for Super-Resolution Microscopy

Labware and Reagents

- Use high-quality #1.5H glass coverslips for optimal resolution. Most super-resolution techniques require extremely flat, low-autofluorescence glass.

ibiTip: Many ibidi µ-Slides, µ-Dishes, and µ-Plates are available with a #1.5H high precision glass coverslip—ideal for all super-resolution techniques.

- If using polymer surfaces, test compatibility first.

ibiTip: When working with the ibidi #1.5 Polymer Coverslip, evaluate your dye and imaging conditions using the ibidi Free Sample Program before committing to large experiments.

- Minimize autofluorescence. Avoid phenol red, fluorescent plastics, or high-background antifades.

Fluorophores and Labeling

- Choose dyes optimized for your modality. PALM/STORM requires photoswitching dyes (e.g., AF647); STED requires dyes that tolerate strong depletion lasers.

- Avoid over- and under-labeling. More labeling does not mean a higher resolution. Over-labeling artificially clusters structures; under-labeling produces incomplete reconstructions.

- Select fixation methods carefully. Methanol fixation destroys many epitopes; glutaraldehyde stabilizes structures but can impair photoswitching.

Buffers and Imaging Media

- Use fresh, stable switching buffers. The blinking buffer can lose activity within 1–2 hours. Prepare fresh buffers and keep samples sealed.

- Reduce oxygen exposure. When exposed to oxygen, scavengers in the buffer can become overloaded resulting in unstable or loss of blinking within minutes.

ibiTip: The closed microchannels of ibidi Channel-Slides reduce oxygen diffusion and evaporation, helping maintain stable blinking buffer conditions for long acquisitions.

- Monitor pH drift. Blinking buffers can acidify during imaging, leading to abnormal blinking behavior.

- Match refractive indices. Mismatches between immersion oil, coverslip, and medium cause severe spherical aberrations.

Microscope Setup

- Choose the appropriate super-resolution modality. Resolution, live-cell compatibility, labeling density, and sample thickness all determine whether STED, PALM/STORM, SIM, or ExM is ideal for your experiment.

ibiTip: Check the overview table comparing the different super-resolution techniques

- Check alignment frequently. Depletion beam misalignment (STED) or pattern misregistration (SIM) is one of the most common user issues.

- Optimize laser powers. Too much laser power causes bleaching; too little prevents good localization statistics.

- Verify PSF quality with sub-diffraction beads. 20–100 nm beads reveal axial elongation, astigmatism, or misalignment.

Data Processing and Analysis

- Validate resolution improvements. Compare your data with known reference structures (e.g., microtubules or nuclear pores).

- Avoid over-processing. Excessive filtering in SIM or incorrect fitting parameters in PALM/STORM can introduce reconstruction artifacts.

- Keep raw data. Many post-processing steps (drift correction, bleaching correction, thresholding) require unprocessed data.

Article written by | Foto |